The transition from open-pit to underground mining (OP-UG) is a critical strategic shift for many large-scale mines. This typically becomes necessary when increasing pit depth leads to an uneconomical stripping ratio, declining returns, or environmental and land constraints.

This decision is far more complex than a simple change in extraction method. Poor planning risks premature resource sterilization, prolonged production disruptions, financial strain, and long-term safety liabilities. Conversely, a well-executed transition can significantly extend mine life, stabilize cash flow, and maximize resource value.

Based on industry best practices, the following eight factors are crucial for a successful OP-UG transition.

Many unsuccessful transitions fail not because the direction was wrong, but because the decision came too late.

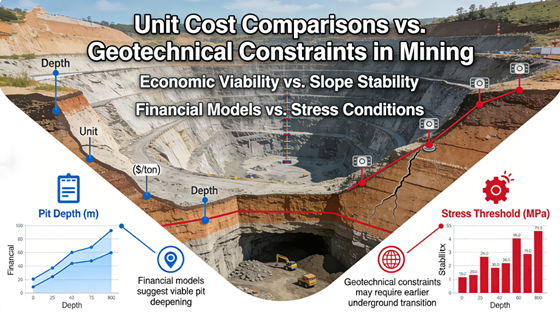

In principle, the optimal transition depth occurs when the marginal cost of deepening the open pit approaches the projected cost of extracting the same ore underground. In practice, geological and geotechnical constraints frequently impose limits well before economics alone would justify a switch.

A widely accepted industry benchmark is to begin OP–UG planning 5 to 15 years before the open pit reaches its ultimate limit. This window is not for observation, but for committing to access development concepts, infrastructure interfaces, production sequencing, and long-term integration with the processing plant. Once the open pit enters its final years, underground development can no longer afford to be reactive.

One of the most common—and costly—mistakes in OP–UG decision-making is relying too heavily on cost per tonne.

A robust technical-economic assessment must consider life-of-mine economics, stripping ratio trends, net present value across alternative development paths, and the timing of capital deployment. The objective is not short-term cost minimization, but long-term value maximization.

Equally important, geotechnical constraints can override purely economic logic. Even where financial models suggest further pit deepening is viable, slope stability or stress conditions may dictate an earlier transition to underground mining.

If there is a single factor that can decisively constrain an OP–UG transition, it is geotechnical performance.

Crown pillar design plays a critical role in separating open pit and underground workings and maintaining overall stability. Errors in thickness or reinforcement strategy can have irreversible consequences. Rock mass characterization—using systems such as RMR, Q, GSI, or Hoek–Brown parameters—is not academic formality; it directly governs underground feasibility and method selection.

A clear understanding of rock strength, structural fabric, and in-situ stress informs both slope design and underground excavation strategy. Experience consistently shows that earlier geotechnical modeling leads to lower transition risk and greater design flexibility.

Different underground mining methods impose very different demands on the rock mass.

Competent, well-structured rock may support room-and-pillar or sublevel open stoping. More variable or weaker conditions often favor backfill-based methods. In selected large ore bodies, caving methods may offer scale advantages, but only where geological and operational prerequisites are fully met.

The critical point is not whether a method is considered advanced, but whether it can reliably deliver safety, productivity, and cost control throughout the underground mine’s life.

One of the most underestimated challenges during an OP–UG transition is maintaining production continuity.

As open-pit output declines and underground production ramps up, any mismatch can disrupt mill feed and place immediate pressure on cash flow. Without early coordination, this gap tends to widen rather than resolve itself.

Successful transitions typically synchronize open-pit drawdown with underground ramp-up, accelerate access and development schedules, and optimize combinations of declines, shafts, and adits to minimize idle time. In OP–UG projects, production curves matter more than peak tonnage.

In many OP–UG projects, delays are driven less by mining methods than by supporting systems.

Access layouts set long-term productivity limits. Ventilation design is critical in confined underground environments, where insufficient airflow or exhaust recirculation quickly becomes a safety and efficiency issue. Water management is equally decisive; pit inflows during wet seasons can migrate into underground workings through fractures or voids, with severe consequences.

Where open-pit and underground operations overlap, blast timing and vibration control must be carefully coordinated. Early decisions on whether the final pit will support underground operations or be rehabilitated independently also have far-reaching implications.

While OP–UG transitions are often framed as engineering problems, they are equally human ones.

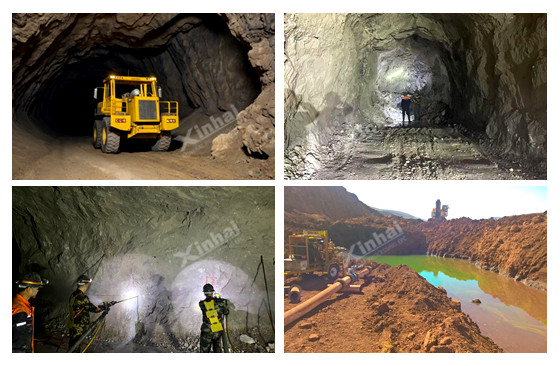

Underground mining demands a fundamentally different skill set, safety mindset, and equipment familiarity. Large surface haulage fleets give way to LHDs, drilling jumbos, and specialized support equipment. At the same time, safety monitoring and emergency response systems must be upgraded.

Phased workforce transition—allowing people, equipment, and systems to evolve together—tends to deliver more stable operations and stronger organizational confidence.

In many jurisdictions, open-pit and underground mining fall under different regulatory frameworks. OP–UG transitions frequently require updated environmental and social impact assessments, revised safety studies, and amended mining permits.

Experience shows that early engagement with regulators significantly reduces uncertainty. Leaving permitting adjustments until late design stages often results in avoidable delays and cost escalation.

Conclusion: OP–UG Is a Systems-Level Decision

The OP–UG transition is a classic multidisciplinary engineering challenge. Success requires a holistic approach that integrates mining, geotechnics, processing, and economic strategy. These considerations are best addressed through integrated mining solutions covering mine design, engineering, and project implementation.

Experienced mining partners provide the total system support needed for these projects—from geotechnical modeling and feasibility studies to infrastructure and onsite supervision.

Are you planning an OP–UG transition? Connect with Xinhai Mining. We provide global mining operations with specialized technical support across the entire value chain.

Share your project details and our engineers will get back to you shortly.